Sintesi

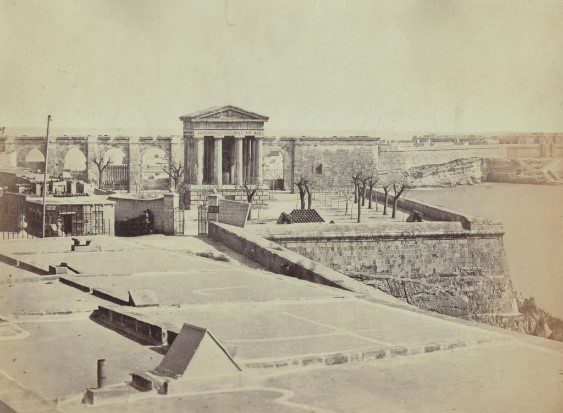

From the Lower Barrakka Gardens, like the Upper Barrakka, one can enjoy breathtaking views across the Grand Harbour. Several monuments erected since the time of the Knights could be observed namely the Three Cities, Villa Bichi, Fort Ricasoli, as well as recent ones including the breakwater and the Memorial Siege Bell. This garden was one of the first monuments that many travellers coming to Malta on their Grand Tour saw once they approached the entrance of the Grand Harbour. In 1830, Pericciuoli Borzesi in his historical guide dedicated to Henry Ponsonby, the son of the Governor of the time Sir Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby, described this garden as the most delightful place overlooking the mouth of the Grand Harbour - the place “where ships on entering the [Grand Harbour] seem almost to come within reach of the hand”.The Lower Barrakka occupies the St Christopher Bastion close to the Sacra Infermeria. It originates in ca. mid-17th century, and was possibly constructed before the Upper Barrakka Gardens. This is hinted by its colloquial name, barracca vecchia, which the contemporary community had assigned to it over the years. Similar name was assigned to the Upper Barrakka, barracca nuova, (owing to it being constructed after the lower garden), which was modified into a place of recreation for the Italian knights in 1661 by the Grand Prior of Messina, Fra Flaminio Balbiani. At the Lower Barrakka, a series of roofed arcades overlooking the entrance to the Grand Harbour were built at the inner part of the garden.

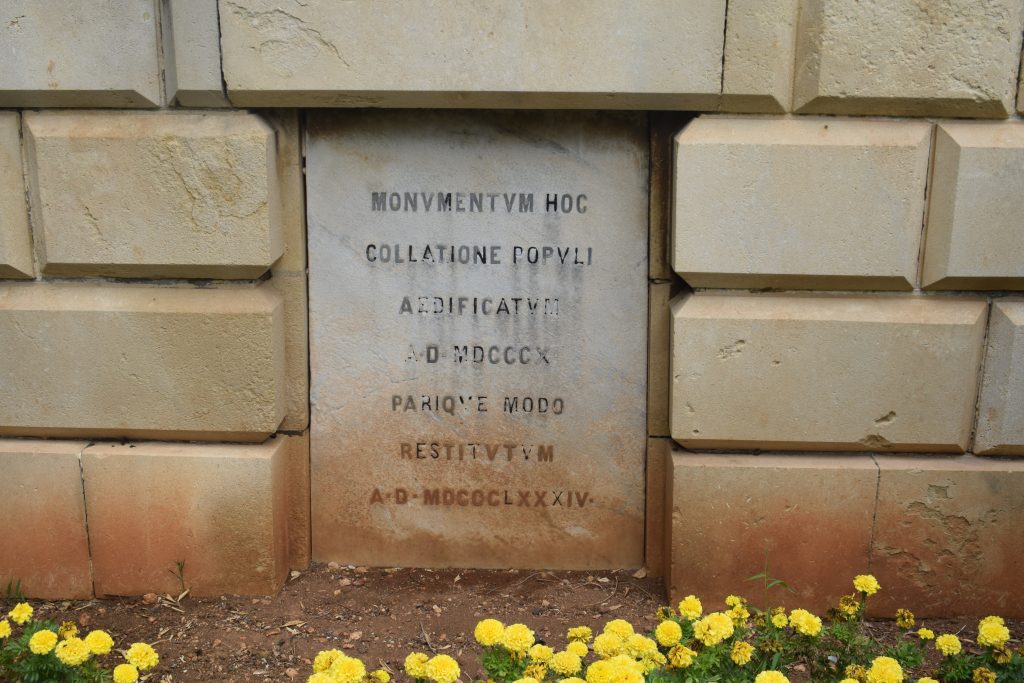

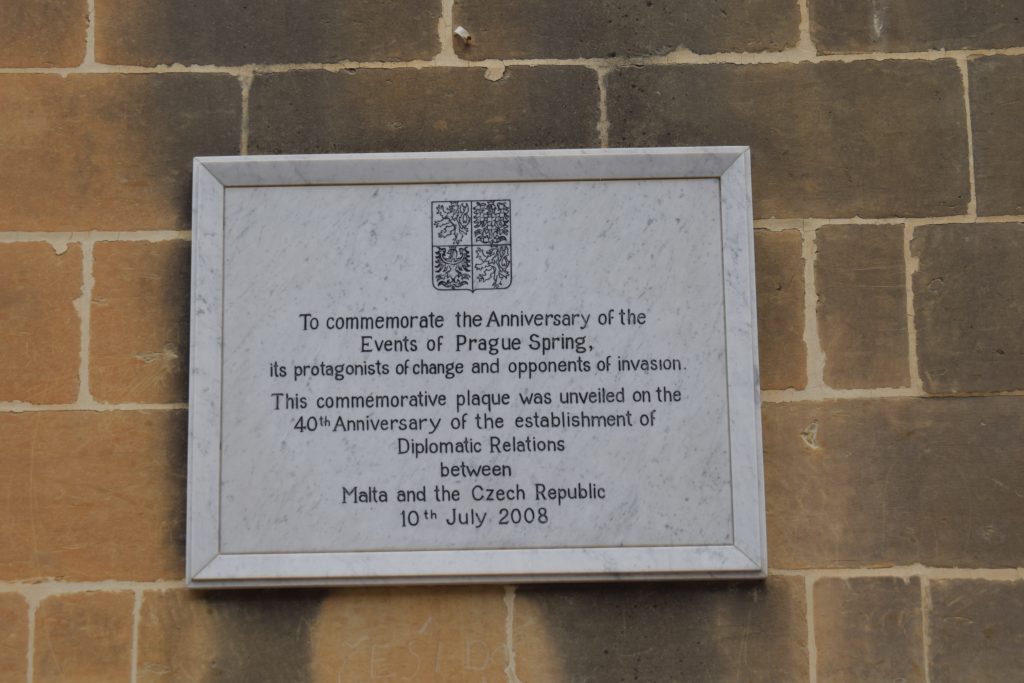

It was during the first few years of the British period that the Lower Barrakka attained increasing attention, especially once the monument of Sir Alexander Ball, was erected at this garden. Ball’s monument was placed at the centre part of the Lower Barrakka Gardens, and since then this monument became the most intriguing element at this garden. It was the first isolated structure erected in a wide open space, that experimented novel concepts of Romanticism in Malta integrating the structure with the surrounding landscape. The Lower Barrakka, as were also other points on the Valletta fortifications such as the Upper Barrakka and Hastings Gardens, were seen as landmarks for the diffusion of ideas on heroism which turned these gardens into the best places for the erection of memorials in commemoration of British military leaders and admirals. (Borg 2001, 35) Such places were chosen for their recognition as areas of social gathering and points of reference within the city. Ball’s monument in fact attained special political significance becoming the emblem of British sovereignty over the Maltese islands; to the extent that in 1815, a building on Mediterranean Street (close to the Sacra Infermeria) was demolished because it obstructed views towards Ball’s monument. This made the Lower Barrakka Gardens a prominent landmark and a subject much acclaimed by many landscape painters. Soon after Ball’s death, a committee was formed to discuss the creation of a public memorial. Within the same year of the Commissioner’s death, the Maltese architect Giorgio Pullicino (1779-1851) submitted his design for a mausoleum. The design of this monument was initially attributed to Pullicino by Zammit (1929, 82), Simpson (1957, 77), and later Ellul (1982, 13), although Faurè refers to the British architect and Commandant of the Royal Engineers, George Whitmore (1775-1862), as the architect of Ball’s memorial. In 1802, Pullicino was appointed professor as soon as the British had established the course of architecture and drawing during the same year within the University in Valletta. Ball’s and Pullicino’s good relations are well known, in fact Pullicino had worked for Ball as soon as the architect returned from Rome in 1800 and it was Ball who suggested Pullicino’s nomination for professor. Ellul (1982, 13) disagrees with Faurè’s attribution to Whitmore since according to archival documents at London, the British architect arrived in Malta in February 1812, two years after the monument was already built. On the other hand, however, Whitmore himself claims authorship for this monument in his memoirs. It seems that Whitmore had undertaken some modifications to Ball’s memorial.The site of the Lower Barrakka was chosen for the erection of the monument, following which a public subscription was issued allowing the building of Ball’s memorial in 1810.Soon after the erection of Ball’s monument, the Lower Barrakka was landscaped and in 1821 was converted into a public garden. It was later extended onto the Castille Bastion, where today there is the Siege Bell Memorial. The fountain in front of Ball’s monument and pathways were added in the late 19th to early 20th century. In 1979, the Lower Barrakka was cut off from the fortifications below it after the new circular road was constructed. Several other commemorative plaques are today found at various parts of the Lower Barrakka including that for the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the Prague Spring, Giuseppe Garibaldi and the 50th Anniversary of the European Union.

Ball's monument was restored in 1884. The works were funded by public subscription, which had also funded the original building of the monument in 1810.The unroofed arcaded structure referred to as the 'barracca' was extensively rebuilt in the 1980s.The garden paving and facilities were replaced and upgraded in the early 2000s.

Ball’s memorial was a Grecian neo-Doric styled temple. It was formed of a solid naos enclosed by a peripteral tetrastyle colonnade that adorned the four sides of the structure, which was raised on a high stylobate. This was the first manifestation in Malta of the British new fashion and their cultural tastes. Pullicino’s design in the neo-classical style followed that of the Temple of Theseus in Athens, albeit on a much smaller scale and of a different shape.

- Borg, Malcolm, British Colonial Architecture Malta 1800-1900, Malta 2001, p. 33-35.

- Bonnici, A. ‘Gonna u Monumenti’, Lehen is-Sewwa, Saturday 18th March 1978, p. 2

- De Lucca, Denis, ‘Some Landmark Buildings of Valletta’, in Encounters in Valletta A Baroque City through the ages, Petra Caruana Dingli, Giovanni Bonello, Denis De Lucca eds., Malta 2018, p. 77.

- Ellul, Michael, ‘Art and Architecture in Malta in the Early Nineteenth Century’, in Proceedings of History Week 1982, Mario Buhagiar ed., Malta 1983, 1-19 (p. 13)

- Faurè, Giovanni, Li Storia ta Malta u Ghaudex bil gzejjer taghhom, vol. iv, cap. iii, sec. i, Malta, 1916, 158.

- G.F. Gemelli Careri, Giro del Mondo, 6 vols., Napoli 1699. Lib. I Cap. II, p. 17

- Mangion, Fabian, ‘Andrea Vassallo: the self-made brilliant architect’, The Sunday Times of Malta, 20th January 2019, p. 56-7.

- Mifsud, Christian and Spiteri, Mevrick, ‘Ta’ Liesse. Reading Transformations at the Water’s Edge. Maritime Spaces, Archaeology and Urban Harbourscapes’, in Ta’ Liesse. Malta’s Waterfront Shrine for Mariners, Giovanni Bonello and Raymond Miller eds., Malta 2020, 73-107. (p. 80-3)

- Simpson, Donald H., ‘Some public monuments of Valletta 1800-1955’, Melita Historica, 2, 2 (1957), 73-86. (p. 77)

- Whitmore, George, The general - the travel memoirs of General Sir George Whitmore, Joan Johnson (ed.), Gloucester 1987.